And suddenly there was a porcelain pavilion

Jonathan Nott conducts two East Asian-inspired works: Messiaen's "Sept haïkaï" and Mahler's "The Song of the Earth". Both composers discover above all themselves in exchange with the foreign.

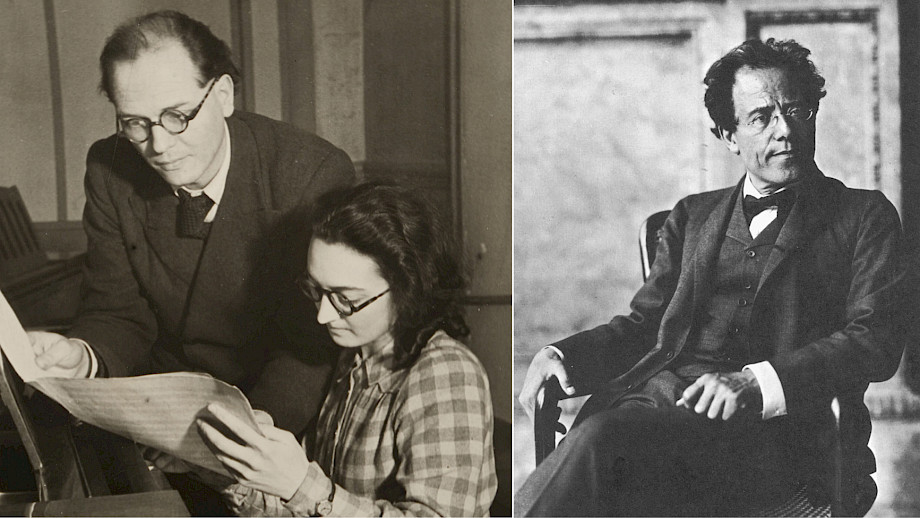

The vermilion red stands out from the sea and the surrounding landscape from afar, and at low tide you can see it up close: the sixteen metre high torii on the Japanese island of Miyajima. It is one of Japan's biggest tourist attractions and the postcard motif par excellence. Torii are sacred gates and stand at the entrance to Shintō shrines. They mark the border between the profane and sacred worlds and show the gods the way to the temple complex. Olivier Messiaen (pictured left with his wife Yvonne Loriod) must have also seen the red torii on his honeymoon in 1962 and felt inspired by the sight - so much so that he chose it as the title of the fifth movement of his work "Sept haïkaï. Esquisses japonaises ", which premiered a year later.

This is not a haiku

Anyone who thinks that Messiaen's "Sept haïkaï" is a setting of short Japanese poems is mistaken. You will search in vain for a vocal part or the 5-7-5 structure typical of haiku. As a rule, haiku consist of three verses, with the first having five, the second seven and the third again five mores - syllable-like units. However, with the additional indication in the title "Esquisses japonaises" (Japanese sketches), Messiaen skilfully created a space for himself, as the sketchy, unfinished, fragmentary nature of the work cannot really be squeezed into a form - especially not one as narrow and minimalist as that of the haiku.

From the second to the sixth movement, various locations in Japan are thematised, including Nara, Miyajima and the ornithological dream destination Karuizawa, which Messiaen, a bird lover, portrayed with the orchestral imitation of numerous bird calls. The fourth movement is an exception: "Gagaku" is not a place, but a form of Japanese court music that has its origins in the seventh century. Literally, it means "elegant music". The shō, a mouth organ with seventeen bamboo pipes, and the hichiriki, a reed instrument, are integral parts of gagaku music. Messiaen imitates the shō with the use of eight violins playing sustained eight-part chords - and the role of the hichiriki is given to the trumpet.

Messiaen's closeness to nature and his love of musical experimentation made him receptive to an encounter with Japan. Perhaps he would have got on well with Matsuo Bashō (1644-1694), probably the most famous haiku poet: In his poems, he captures brief moments in nature in which smells, sounds and colours take on a central role.

This synaesthetic approach can also be found in Messiaen, who worked intensively on the translation of phenomena into musical language. In an interview in 1979, he said that he sees colours when he hears music. In the fifth movement, "Miyajima et le torii dans la mer", he attempts to capture the colours he saw on the island in his music: "The green of the Japanese pines, the white and gold of the Shintō shrines, the blue of the sea and the red of the torii - I wanted to translate that [...] almost literally." Messiaen creates a portal between the world of colour and the world of music - similar to how the torii functions as a connection between secular and sacred space.

A trendy gift

in 1911, around half a century before the premiere of Messiaen's "Sept haïkaï", the premiere of Mahler's cycle "The Song of the Earth" took place. He too was inspired by East Asia, in this case China. Unlike Messiaen, however, he had never been there.

In 1907, Mahler had received a book of poems by Hans Bethge entitled "The Chinese Flute" as a gift from his friend Theodor Pollak, in which the composer found the basis for the text of his work. Such a gift was in vogue at the time: from the 1890s to the 1910s, there was a veritable boom in translations of Chinese literature and poetry. New publications on Chinese history, geography and culture also appeared on the market. This interest was partly a result of the Vienna World Exhibition of 1873, which sparked the curiosity of Western visitors for East Asian art.

A thousand year old whisper game

Mahler used seven poems translated into German for the song text, the roots of which go back to the Tang dynasty. Mahler's song text could be described as the product of a whispered message that is over a thousand years old. In this children's game, a message is passed on in a whisper and the end result is often a statement that is so altered that it has almost nothing to do with the original content.

Hans Bethge, who did not understand Chinese, referred to another German translation by Hans Heilmann in his volume of poetry. This in turn was based on two French translations from the 1860s: one close to the text by the sinologist Léon d'Hervey de Saint-Denys and a very free, amateurish one by Judith Gautier. The latter did not speak Chinese very well and used the originals more as inspiration for her own product. Gautier drew a romanticised image of China with motifs such as the moon, jade and porcelain. Ironically, her texts were much more popular than those of the sinologist.

It is therefore only natural that errors crept into these translations, which can still be seen today in the lyrics of the song cycle "The Song of the Earth". In the third movement "Von der Jugend", of all places, which together with the fourth movement is understood as the starting point of Mahler's musical chinoiseries, there is talk of a "pavilion of green and white porcelain". Mahler took this verse directly from Bethge. However, if you go back a few steps in the "Flüsterpost", you realise that Gautier's translation was incorrect here. The Chinese original never mentioned porcelain. Gautier had misinterpreted the Chinese character "陶": It actually stood for the surname Táo, not for porcelain.

"Authentic" pentatonic

Literally, the title was "A Feast in Mr Táo's Pavilion" and not "The Porcelain Pavilion", as it was then called by Bethge. Mahler changed the title to "Von der Jugend". The mainly pentatonic design created a supposedly "authentic" overall product that fits well with the porcelain pavilion and seems to transport one directly to China - or at least to Mahler's idea of it.

Mahler created his own material interweaving from Bethge's text. He added poetry, deleted and rearranged as he saw fit. "The Song of the Earth" marks his final creative phase and does not claim to be a homage to Chinese poetry. His exploration of themes such as farewell, decay and world-weariness, which are reflected musically in his abandonment of tonality, among other things, allow a deeper insight into his emotional state at the time.

Now these two results of East Asian inspiration meet in concert. They will be conducted by Jonathan Nott, who is standing in for Franz Welser-Möst.

We use deepL.com for our translations into English.