"Lullaby of death"

There are few things that say as much about a work as the composer's words. What did Gabriel Fauré say about his famous Requiem? And what is behind the quotes?

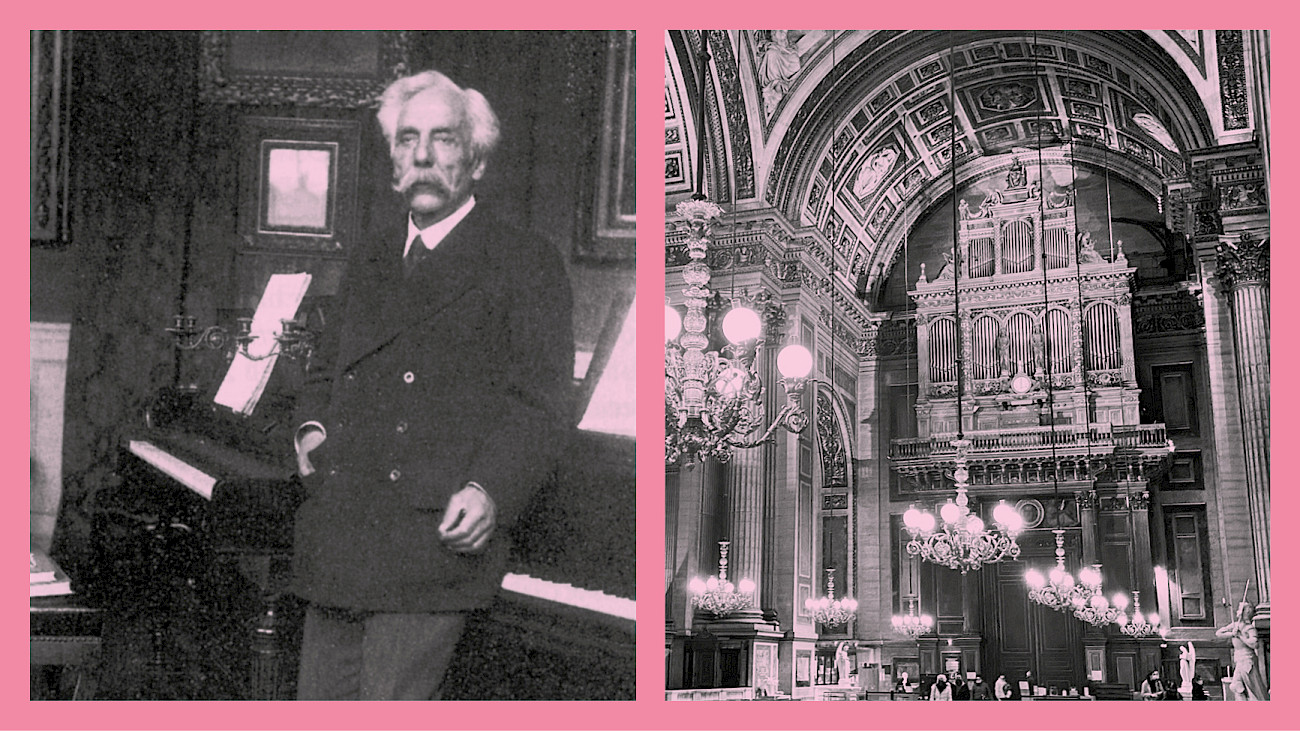

It is probably Gabriel Fauré's most popular work: the Requiem op. 48, but the musician left behind hardly any sketches that would reveal anything about the composition's genesis. As a result, many of the questions we ask ourselves about it today must remain unanswered. However, we are not completely in the dark: in letters and conversations, Fauré made some fascinating statements about his Requiem, which also reveal something about the character of the great French composer.

"My Requiem was composed 'without occasion' ... for my own pleasure, if I may say so! It was first performed around 1890 in the Madeleine for a funeral service for some parishioner. That's all I can tell you!"

These lines, which Fauré wrote to the French musicologist Maurice Emmanuel in March 1910, are as informative as they are provocative. Did he really create a requiem mass for "pleasure"? It is more likely that an external occasion inspired him to write his work. After all, his father had died in 1885 and his mother in 1887. It was precisely at this time that he was working on his Requiem.

Gabriel Fauré had been cantor at La Madeleine parish church in Paris since 1877 and became organist at the main organ in 1896 - a job that he did not always enjoy and often felt was a burden. After all, the church was not really his world: Fauré was an agnostic. Nevertheless, he wrote a Requiem, which at the time - on 16 January 1888 - was not "performed for the funeral of any parishioner", but at the solemn memorial service "first class" on the anniversary of the funeral of the architect Joseph-Michel Le Soufaché, who had been involved in the rebuilding of the Palace of Versailles ordered by Louis-Philippe I, among other things.

And Fauré left out even more in his letter to Emmanuel: Namely, he revised the Requiem several times over a period of 14 years and therefore created different versions. The highlight was probably the performance in 1900, when the final version of the work was played in front of an audience of around 5,000 at the Paris World Exhibition.

"Perhaps I instinctively tried to escape the conventional. I've been accompanying funeral masses on the organ for so long! I've had enough of that and wanted to do something different."

Fauré's words from 1902 clearly reveal the composer's boredom and frustration. The latter must have intensified after the Requiem's premiere. The vicar approached him and simply said: "Monsieur Fauré, we don't need all these innovations; the Madeleine's repertoire is rich enough." The liberating feeling of finally no longer being trapped in the same repetitive loop quickly gave way to anger. The opéra comique style was considered the ultimate at the time - even in church services. Fauré, on the other hand, wrote more intimate music. He worked with the musical material of his Requiem in a more chamber-music style.

This attitude of the vicar and Fauré's understanding of music may be the reason why the composer, although he was in the service of the Catholic Church for a total of 40 years (1865-1905), only wrote 26 church music works and no organ music. With the exception of his Requiem, these are almost all short compositions. And only ten of them were composed in the almost thirty years in which Fauré was employed by the distinguished parish of La Madeleine.

"It has been said that it expresses no fear of death; someone has called it a 'lullaby of death'. But that's how I feel about death: as a happy liberation, as the pursuit of happiness in the hereafter rather than a painful transition."

The Requiem has several special features. These include a positive and comforting mood, as Fauré omitted the "Dies irae" ("Day of Wrath") - and thus the climax of many requiems, such as those by Mozart or Verdi. But that's not all: Fauré added a new section at the end. The requiem ends not with horror ("Dies irae"), but with paradise ("In paradisum"), which is traditionally sung when the body is transferred from the church to the cemetery. Fauré's above statement about his Requiem thus captures both the essence of the work and that of his personality. And so it was probably a matter of course that the Requiem was played at Fauré's funeral in 1924. After all, he was of the opinion that it was "of a gentle character, like myself".

"Super flumina Babylonis" (Psalm 136)

Gabriel Fauré (1845-1924) was an important innovator of French music, an excellent organist and also an outstanding teacher (of George Enescu, Nadia Boulanger and Maurice Ravel, among others). In recent years, he has gradually been rediscovered and his works are being played more frequently again. But there are still rarities, and with "Super flumina Babylonis" Paavo Järvi juxtaposes one of them with the famous Requiem. The setting of Psalm 136 for soprano, tenor, mixed five-part choir and orchestra was the first church music work that Fauré composed. He wrote it in July 1863 for the end-of-year competition of the École de musique classique et religieuse. It was well received by the jury: it was rated "very honourable", and the music critic of the "Ménestrel" described it as "extremely remarkable". "Super flumina Babylonis" is special in many respects: It is one of the three great works of church music that Fauré composed (followed two years later by the composition "Cantique de Jean Racine", and only 14 years later by the Requiem) and a testimony to his early style, which is still reminiscent of Brahms or Berlioz.

Translated with DeepL.com