What Kind of Music Blows Fuses?

György Ligeti's «Volumina» pushes organs and organists to their limits. Christian Schmitt plays the piece nevertheless.

Christian Schmitt can well remember his first performance of Ligeti's epochal organ work "Volumina", which took place in the Bamberg Concert Hall in 2004. He also remembers the phone call from the hall's titular organist, who warned him before the concert not to break his organ.

The warning did not come by chance. The premiere of Ligeti's masterpiece in Bremen Cathedral was cancelled in 1962 after a smouldering fire broke out during a rehearsal in Gothenburg. A few years later, there was also an incident in the French Church in Bern: when organist Guy Bovet was practising "Volumina", all the fuses blew. Here, too, the performance was cancelled.

The piece was indeed dangerous for the instruments, says Schmitt. But why, actually? The answer can already be found at the beginning. All the stops are to be pulled and all the keys and pedals of the organ, which is still silent at first, are to be pressed. Then the motor is switched on, and out of nowhere the sound builds up - if the instrument can withstand this enormous strain.

"Something between sound and noise"

For Ligeti, however, this beginning and the rest of this radical work were not about a test of strength, but about discovering new musical territory. "I experimented a lot to see what I could get out of this almost dead instrument", he said in an interview with the music journalist Josef Häusler in 1970, "and I found that there was quite a lot to discover".

What he discovered he himself described as "empty form", as "neutralised sound", as "something between sound and noise". There are neither melodies nor harmonies in the work, nor any rhythm. They are clusters, balls of sound that push through the space in "Volumina"; in the process, the "labyrinthine movements" (Ligeti) are shaped not only with the fingers and feet, but also with the whole palms or forearms.

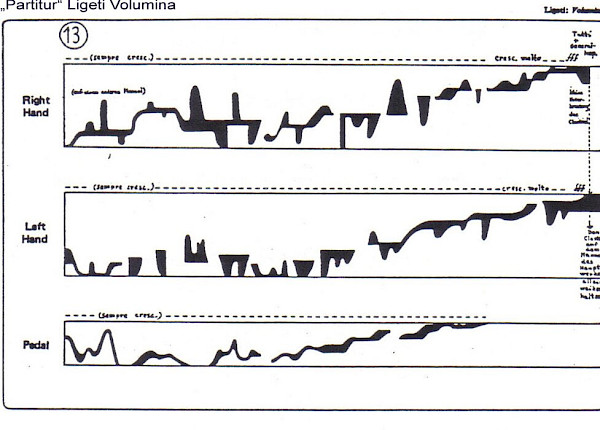

The score does not prescribe any details for this; it is graphically designed, with bands that stretch across the pages, becoming wider and narrower, swinging up and down, fraying, breaking off. The movements are predetermined, but not the pitches and durations. In this way, as Ligeti said, "figures without a face emerge, as in pictures by de Chirico, vast expanses and distances, an architecture that consists only of scaffolding, but lacks a tangible building".

Through space and time

In other words, sound spaces are created that are constantly changing. And a time stream is created that carries you through these spaces. Ligeti had concrete ideas about this, not only in terms of sound but also visually: For him, the concept of "time" was "misty-white, flowing slowly and inexorably from left to right, producing a very quiet, hhh-like sound", the composer told Josef Häusler in the interview. On the left side there is "a violet place with a tinny texture and sound"; the right side, on the other hand, is "orange, has a skin-like surface and a muffled sound".

However these ideas are concretely realised: Even 61 years after its composition, a performance of "Volumina" is and remains an adventure - for the audience, for the performers, for the organ. Now the work is being performed for the first time on the Kuhn organ in Zurich's Tonhalle, which was inaugurated in 2021. Is it now in danger? Christian Schmitt waves it off. He has played the piece, which lasts about 16 minutes, in various places since the Bamberg performance without ever causing a fire. And he assures us that he will be careful this time as well.

Translated with DeepL.com